Interpretations for Predicate Logic

Author: Billy Price

Models vs Interpretations Terminology

In the field of logic, the term model has two strengths of meaning. In the weaker one, to say “$M$ is a model” is just to say that $M$ is just a configuration of the world - in which some formula might evaluate to true or to false. However, in the context of a particular formula, $\varphi$, the statement “$M$ is a model for $\varphi$” or “$M$ models $\varphi$”, often takes on the stronger meaning, which is, $M$ is a configuration of the world, and in that world, $\varphi$ is true. To make the negative statement, we might say “$M$ is a countermodel of $\varphi$”, meaning $M$ is a configuration of the world in which $\varphi$ is false.

Under the weaker meaning of model, we would typically have to say “$\varphi$ is true in the model $M$”, if we wanted to make this stronger statement. From this point forwards we take the stronger meaning of model, and we name the underlying configuration an interpretation. So to say that “$\mathcal{I}$ is an interpretation of $\varphi$”, just tells you that it is a configuration of the world which tells you what all the symbols in $\varphi$ mean. We could go further and say that “$\mathcal{I}$ models $\varphi$”, meaning $\varphi$ evaluates to true under the interpretation $\mathcal{I}$.

The notions of logical equivalence and consequence, validity, satisfiability, non-validity and unsatisfiability all carry over to predicate logic - we just replace the word model with interpretation, and say something like “every/some interpretation $\mathcal{I}$ is/isn’t a model for $\varphi$. The main difference is that now have a much more general notion of interpretation.

What is an Interpretation?

The primary data of an interpretation is a domain, $D$, which is a non-empty set of objects ($D \neq \emptyset$). The interpretation then decides the meaning of all of the following

- constants - a fixed object from $D$ for each constant

- function symbols - a function $D^n \to D$ (where $n$ is the arity of the function symbol)

- predicates - a function \(D^n \to \{\mathbf{f}, \mathbf{t}\}\) (where $n$ is the arity of the predicate). We often conflate $\mathbf{f}$ with $0$ and $\mathbf{t}$ with $1$ when specifying the interpretation.

Interpretations are also accompanied by valuations, which take care of free variables (assigning them to objects), but we typically work only with closed formulas (no free variables). This is why “$\mathcal{I}$ models $\varphi$” actually requires us to check all possible accompanying valuations, in case there are free-variables, but we can ignore this when just working with closed formulas. There is quite a bit of subtlety involved in exactly how we compile formulas to truth values - mostly dealing with variables under quantifiers - see the week 4 slides for how this is done.

To claim a formula is true in every interpretation (i.e., valid), we must show it is true for every domain, $D$, every interpretation of the constants as objects in $D$, every interpretation of the function symbols as functions $D^n \to D$, every interpretation of the predicates as functions \(D^n \to \{\mathbf{f}, \mathbf{t}\}\) (one notable exception to this rule is the predicate “$=$”, which we always interpret as true of two objects exactly when they are the same object). This should strike you as a big task - we can’t just list all the interpretations, like in propositional logic, since there are infinitely many domains! We will use a generalised resolution method to do this.

On the other hand, establishing that one interpretation agrees or disagrees with some formula can be much simpler.

How do I write down a particular interpretation?

A interpretation in predicate logic has various pieces of data, which you can just state in sequence, and omit anything unecessary (for example, if your formulas have no function symbols). There is no strict way you should be packaging all of this data, just make it neat, clear, and most importantly complete.

- Write down a domain. For example \(D = \{a,b,c\}\), or $D = \mathbb{Z}$.

- If there are any constants in your formula, either include them as part of the domain with the same name, or explicitly define the association. For example, you could declare a domain \(D = \{a,tom,c\}\) and do nothing more, or declare a domain \(D = \{a,b,c\}\) and separately write down constants: $tom \mapsto b$.

- Describe the function interpretations for the function symbols and the predicates

The best way to do Step 3 depends on the size of the $D$.

- Infinite Domains - write down some rule. So if $D = \mathbb{Z}$, you could choose $f(x) = x + 1$ for a function symbol, or $P(x) = (x \text{ mod } 3 \equiv 0) $. For more complicated predicates, just describe exactly when they are true or false of their inputs with sufficient detail.

- Finite Domains - there are a couple options

- List all the assignments - e.g. $f(a) = b, f(b) = a, f(c) = c$, $P(a) = \mathbf{t}, P(b) = \mathbf{f}, P(c) = \mathbf{t}$.

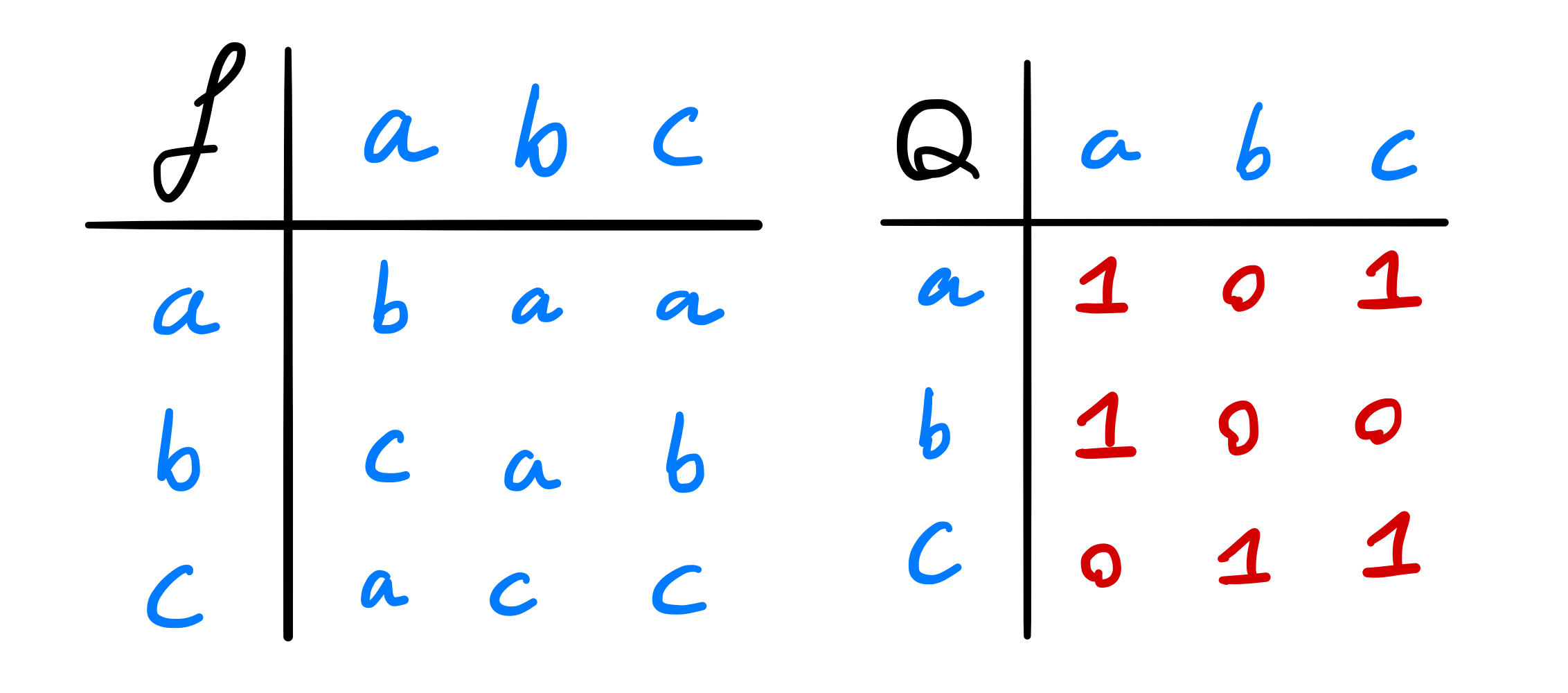

- For binary functions or predicates, write down a table, where the rows determine the first input and the columns determine the second input. The below example specifies $f$ and $Q$ such that $f(a,b)=a,~ f(b,a)=c, \dots, ~ Q(c,b)=1,~ Q(b,c)=0, \dots$

Notice that in listing or tabling the assignments of objects to other objects (or truth values), there may or may not be some concise rule like $f(x)=x+1$ or “$P(x)$ is true iff. $x$ is even” (especially if the domain is abstract, like $D={a,b,c}$). This is fine, because here, what a function is, is the assignments, not a rule. We are of no obligation to make sense of the assignments - they just are. In fact, there are many many functions for which there is no finitely specifiable rule that produces the outputs from the inputs.

Tips

When crafting a interpretation that agrees or disagrees with some formula, here are some tips.

- Try to think of the smallest possible non-empty domain you could use, and just pick some anonymous names for your objects like $a,b,c,d, \dots$. Start with a one element domain, then two, then three and so on.

- Just because you have an $n$-place predicate or function symbol, doesn’t mean you need $n$-many objects. For example, $D = {a}, P(a,a,a) = \mathbf{t}$ describes a interpretation which models $\forall x~(\exists y~(\forall z~(P(x,y,z) \Rightarrow P(x,z,y))))$.

- If none of your small domains work, give up and try $D = \mathbb{N}$ or $D = \mathbb{Z}$ (the natural numbers and the integers), and some creative intepretation for the predicates and function symbols.

- Make sure your function definitions are complete. Is there any possible inputs to your functions or predicates for which you haven’t specified an output/truth value? Even if these values don’t change whether your formula is true or false in the interpretation, it is best to present a fully realised interpretation to avoid error, and to remove any doubt that your interpretation is a model.